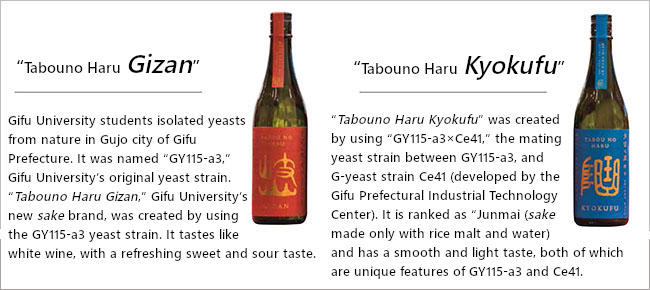

Gifu University's new sake brands fermented by the university's original yeast strains isolated from natural environments in Gifu

*Information related to faculty members/students and graduate schools at Gifu University here are all that of the time of interviewing.

Selection of original sake yeast strains isolated from natural environments based on the unique aroma produced by the yeast.

by the Faculty of Applied Biological Sciences: students planted and harvested

"Hidahomare" rice variety for sake.

I became quite interested in making sweets when I was in junior high school. Soon, I discovered the many scientific aspects of sweet making. For instance, when baking powder is used, the composition of ingredients determines the quality of sweets, among other things. Being intrigued by the many mysteries regarding food, I decided to study the Life Science for Food, Faculty of Applied Biological Sciences, Gifu University.

I studied a wide range of food-related subjects for four years at the university. They included food nutrients, food's health-promoting functions, food production, processing, preservation, distribution, and marketing. I was particularly attracted by food microbiology.

Microorganisms are invisible to humans, but play many important roles in food production and consumption. For example, they are indispensable in making fermented foods, such as cheese, miso bean paste and so on.

In the second semester of my third year at the university, I joined a food microbiology lab with the hope of unraveling some of the mysteries of microorganisms.

Association, students are engaged in fermentation

at a brewery in Gifu.

In the lab, I am conducting research on microorganisms, especially sake yeast-one of crucial elements in sake brewing.

In the process of brewing, the sake yeast generates alcohol, organic acids, and flavors; all these give sake distinctive rich tastes. Because of the unique characteristics of the sake yeast, however, it is very important for any brewers to select the right types of sake yeast strains for brewing.

Many brewers in Japan use "kyokai yeast strains (certified and distributed by the Japan Brewers Association)" because of their potent alcohol fermentation. The reason why I seriously started to contemplate producing a new type of sake using the yeasts isolated form natural environments is that I wanted to break away from this notion of using kyokai yeast strains.

Project report session

I paid special attention to the unique flavors generated from yeasts. Yeasts make sake taste mild and fruity, and their fermentation usually determines the grades of sake. However, yeasts also generate a substance called "4-VG," which emits smoky smells; this is a key factor that adversely affects sake grading. The fact that yeasts found in nature produce strong 4-VG during fermentation remains a major obstacle for the production and commercialization of any new sake brands made from the wild yeasts. My research goals were to understand the mechanisms of 4-VG production at the molecular level, select the suitable yeast strains for sake brewing, and breed the yeast strains lost ability to produce 4-VG.

Lab members' strong commitment to the success of the Gifu University Sake Project

The major purpose of the "Gifu University Sake Project" was to create a new sake brand for the university by using: 1) "Hidahomare," an original rice variety cultivated by the Gifu university students; 2) "Nomiyasui" groundwater that flows across the campus; and 3) the university's original yeast strains. It was a student-led project involving many stakeholders, including the staff of the Gifu Prefectural Research Institute for Food Sciences, Gifu Prefecture Brewers Union, Japan Agricultural Cooperation Gifu, and the "Kuramoto Yamada" brewery in Yaotsu town of the Gifu prefecture.

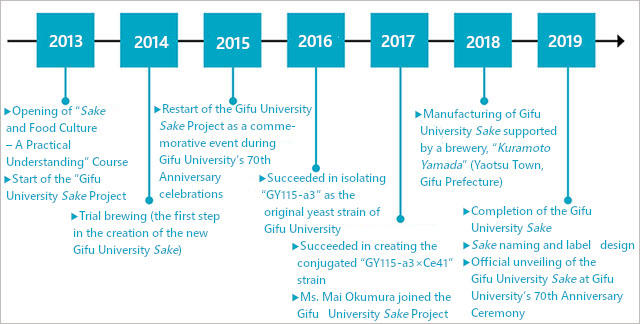

As a matter of fact, the Gifu University Sake Project was originally an extension of the Gifu University "Sake and Food Culture - A Practical Understanding" course taught by Professor Tomoyuki Nakagawa, of the Faculty of Applied Biological Sciences.

During this course, students study Japanese sake, local delicacies, and so on, by actually getting involved in sake making.

Senior students who agreed with the proposal to make a new sake brand by developing sake yeasts themselves, had collected over 1,000 samples from nature (soil, flowers, butterflies, etc.). From these, they succeeded in isolating more than 600 yeast strains, but only 28 were found to be useful for sake brewing.

When the president of Gifu University, Hisataka Moriwaki, attended the "Sake Tasting" session, he enjoyed and praised the unique taste of the new sake made from the original yeast strains developed by the students. Moved by the students' strong resolve to make a new sake brand, the president proposed a relaunch of the "Gifu University Sake Project." This marked the official restart of the project.

The major roles of my lab were to select the best yeast strain from the 28 strains shortlisted and make them suitable for sake brewing.

In collaboration with the Gifu Prefectural Research Institute for Food Sciences, we performed various experiments on the 28 strains to determine which of them can induce the best alcohol fermentation and generate suitable aromatic flavors. Finally, the "GY 115-a3" strain found in the Gujo city of Gifu prefecture was selected as the Gifu University's original yeast strain for making the University's new sake brand.

"Tabouno Haru" sake fermented by Gifu University's original yeasts

Development of new sake yeasts by mating between Gifu University's yeast and G-yeast

I took part in the Gifu University Sake Project in 2017 (four years after the launch of the project). My primary assignment was to develop new sake yeasts from the GY115-a3 strain. I frequently went to the library to search for documents, and held many discussions with the staff of the Gifu Prefectural Research Institute for Food Sciences. After much trial and error, we decided to create a new hybrid yeast by mating between the G yeast Ce-41strain (developed by Gifu Prefecture) and the GY 115-a 3 strain. We had high hopes of mating the two strains (Ce-41 is known for its gorgeous flavor, and GY 115-a 3 known for its unique acidic taste) to create a totally new, distinctive yeast.

In the fifth attempt, we succeeded in producing a new hybrid strain. This was followed by the production of eleven different hybrid strains containing the features of both Ce-41 and GY 115-a strains.

All 11 strains turned to have very different fermentation characteristics. Some gave off the flavor of bananas or apples and exhibited large differences in organic acid productivity. We tested all of them to measure their respective fermentation potency, and chose the "GY 115-a3 × Ce-41" strain that induces strong alcohol fermentation and a wonderful flavor. We then asked a Japanese sake brewery in Gifu, "Kuramoto Yamada," to use the GY 115-a3 × Ce-41 for sake brewing. Finally, the first sharp, dry, and less-acidic Gifu University sake brand, "Tabouno Haru Kyokufu" was created.

Development of "Tabouno Haru Gizan" containing the unique acid flavor of GY 115-a3

Another new Gifu University brand sake named, "Tabouno Haru Gizan," with the distinctive acid flavor of GY115-a3.

Here is the chronology of events in the manufacture "Tabouno Haru Gizan."

First, we fermented sake using strain GY115-a3 for 20 days at 14°C, as other brewers do, but the acidity of the fermented sake turned to be so strong that it ruined the sake's flavor and taste. Being stuck in a dead-end situation, we sought advice from the staff of the Gifu Prefectural Research Institute for Food Sciences, and they suggested that we do the fermentation at a lower temperature, as in the brewing of "Ginjo" sake (premium sake made with only the best part of the rice). They said that fermentation at a lower temperature may reduce alcohol content, but add sweetness and maintain the unique acidic taste produced by strain GY115-a3. We followed their advice and set the temperature to 10°C. Finally, we created a new University sake named "Tabouno Haru Gizan," which has a taste of pear (acidic, yet sweet) and tastes more like white wine.

To produce this new "Tabouno Haru Gizan" sake, we worked very hard fine-tuning the fermentation temperatures every day for almost a month; the long, painstaking efforts paid off when we saw the first "Tabouno Haru Gizan" sake being bottled. It was the moment to share the great joy and sense of accomplishment among us in creating something together from scratch.

Through my research activities, I became more interested in sake. I sometimes find myself spending much time reading the labels of sake bottles at places such as shops and stores. Now, I can tell the subtle differences in the taste and characteristics of the sake made by individual breweries.

Chronology of Events leading to the Creation of the Gifu University Sake

Importance of collaboration and thinking things through

70th Anniversary Ceremony in June, 2019.

Dr. Toshio Kuroki, the 10th president of Gifu University, raises a toast to celebrate the 70th

anniversary

The Gifu University Sake Project was one of the biggest projects in which I had ever participated in my life, and from its start to the end, I was made to realize the limits of what I can, and the importance of collaboration with others. I visited the Gifu Prefectural Research Institute for Food Sciences many times to gather information, which helped me learn how to obtain information and exchange opinions on manufacturing or other business sectors.

I must admit that I am a shy person. Although I am not a natural at communicating with people, I had to seek advice from the members of the Gifu Prefectural Research Institute for Food Sciences throughout the Gifu University Sake Project. I now believe that my frequent, active communication with them made me mature as a member of the team.

Thinking things through is also becoming second nature to me since the incident described next. When I made slight changes in the fermentation temperature, I read some hard-to-believe data from the monitoring equipment. No exact values from the equipment were available at that time. Until this incident took place, I was rather optimistic and believed that at the end of the day, I could work everything out. Now, I try to work everything through, and never stop asking until I figure out what is really happening or find solutions to the problems at hand. I am convinced that my sake-making experience has changed me much in a very positive way.

I am thinking of working at fermentation industry in the future. I hope that the expertise and knowledge I acquired through the Gifu University Sake Project can be utilized in sake making.

I am looking forward to working on the development of new value-added products, such as Gifu University Sake, while serving as the proud member of a team.

Faculty of Applied Biological Sciences

Professor Tomoyuki Nagakawa

We have great faith in you!

Hoping that you continue working hard to produce one of the best yeasts in the world

The Gifu University Sake Project was launched in 2013 as a part of "Sake and Food Culture - A Practical Understanding" course of the Faculty of Applied Biological Sciences.

Students in the course did everything from isolating yeast strains, planting and harvesting "Hidahomare"' rice varieties, to sake fermentation. I wish they can use their expertise and knowledge acquired at every stage of sake making at the faculty. I also hope that students of the course will develop their understanding of sake culture in Japan and appreciate it greatly.

One of the major objectives of the project is to get students involved in sake making (from production of raw materials, to manufacturing, processing, and marketing) so that they can learn what the "sixth industrialization (diversification of the primary industry)" really means, and get an understanding of the whole industry.

The participants of the project must have experienced both joy and hardships by being directly involved in sake making. In addition, they must have realized that there are large differences between their products and those made by professionals.

Ms. Mai Okumura played a key role in producing Gifu University's original yeasts with the support of the Gifu prefectural government. I know Ms. Okumura is a person that people can trust and rely on for project implementation and coordination among people.

The yeast strains used for Gifu University's two new sake brands were jointly developed by the faculty and students, and are still in the developmental stage. I am eagerly looking forward to seeing many more excellent new yeast strains developed by my students in the years to come.